| Born | 13 September 1874, Vienna, Austria |

| Died | 13 July 1951 (aged 76), Los Angeles, California, United States |

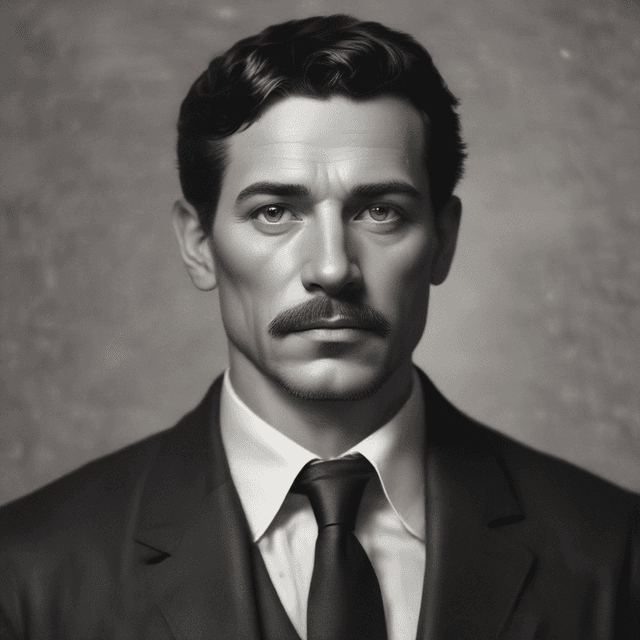

| Name | Arnold Schoenberg |

| Impact | Had a relatively modest impact, with his music remaining on the fringes of the classical tradition |

| Known for | Developing atonality and serial music • Influential music theory writings • Pioneering pedagogue |

| Occupation | Composer • Music theorist • Music teacher |

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) was an Austrian composer, music theorist, and teacher who played a significant role in the development of 20th century classical music. While his radical compositional innovations, including atonality and serialism, failed to gain widespread acceptance in this timeline, Schoenberg's contributions as a music theorist and pedagogue had a lasting impact on the field.

Schoenberg was born in 1874 in the Leopoldstadt district of Vienna, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As a youth, he received violin lessons and was largely self-taught in music theory and composition. In 1889, he began working as a musical assistant and copyist, gaining exposure to a wide range of composers and musical styles.

Despite his lack of formal training, Schoenberg's early compositions, including the 1899 string sextet "Verklärte Nacht," demonstrated a strong grasp of traditional tonality and romantic musical language. This early work, grounded in the late 19th century German tradition, foreshadowed his later, more radical experiments.

In the first decade of the 20th century, Schoenberg began to move away from the tonal system that had dominated Western classical music for centuries. Inspired by the chromatic harmonies of composers like Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss, he embarked on a journey to create a new, emancipated musical language.

Schoenberg's breakthrough came in 1908 with the composition of his momentous "Drei Klavierstücke" (Three Piano Pieces), which abandoned the concept of a tonal center entirely. This marked the birth of atonality, a compositional approach that rejected the hierarchical system of keys and chords in favor of a more ambiguous, free-flowing harmonic structure.

While Schoenberg's atonal works, such as the Five Orchestral Pieces (1909) and the opera "Erwartung" (1909), were hailed by some as groundbreaking, they were also met with widespread bewilderment and hostility from both audiences and critics. The music's lack of a clear tonal foundation and its radical departure from traditional forms were seen by many as inaccessible and even sacrilegious.

In the 1920s, Schoenberg further developed his radical compositional approach with the introduction of the "12-tone technique," also known as serialism. This method involved the systematic organization of the 12 pitches of the chromatic scale into a fixed ordering, or "series," which served as the basis for the entire musical work.

Schoenberg's serialist compositions, such as the String Quartet No. 3 (1927) and the Piano Concerto (1942), demonstrated a high level of structural complexity and intellectual rigor. However, they remained largely on the margins of the classical music establishment, failing to gain widespread popularity or critical acclaim.

Despite the limited impact of his own compositions, Schoenberg's influence as a music theorist and pedagogue was more far-reaching. He founded the Schoenberg School in Vienna, where he taught a generation of composers, including Alban Berg and Anton Webern, who went on to make significant contributions to the development of modernist and avant-garde music.

Schoenberg's seminal treatise "Harmonielehre" (1911), which explored the principles of atonal and serial composition, became an essential text for music theorists and scholars. His ideas and techniques, while not as widely adopted as in our timeline, continued to exert a subtle influence on the evolution of 20th century classical music.

While Schoenberg's radical compositional innovations failed to gain widespread acceptance in this timeline, his role as a pioneering music theorist and pedagogue ensured that his impact was not entirely marginalized. His writings and teachings continued to shape the discourse around musical modernism, even as his own works remained on the fringes of the classical canon.

In the decades since his death, there has been a gradual re-evaluation of Schoenberg's contribution to the musical landscape. His unique synthesis of tradition and innovation, and his unwavering commitment to expanding the boundaries of musical expression, have led to a renewed appreciation for his work among scholars and a new generation of avant-garde composers.

However, Schoenberg's legacy in this timeline remains more muted compared to the outsized influence he exerted in our own. The trajectory of 20th century classical music, and the development of experimental and electronic genres, has followed a markedly different path, with Schoenberg's visionary ideas and techniques playing a less central role in the musical evolution of this timeline.